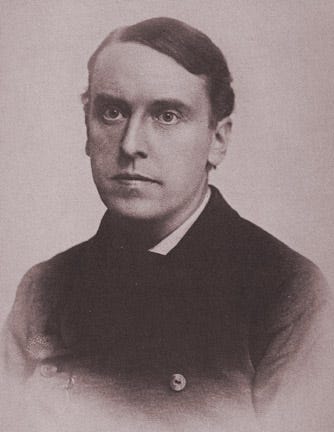

Edward Aveling –

The venom at the heart of the first socialists

Keeping on with my theme of perfidy on the left, here’s a piece about Edward Aveling, a man who betrayed both his beliefs and the people closest to him

The socialist tradition in Britain begins effectively in the 1880s, in the aftermath of Karl Marx’s death. A younger generation of radicals were active in the Social Democratic Federation, Britain’s first Marxist party. Some of the less sectarian were about to split to the left, to join a new party the Socialist League – the parent (via anarchism and class struggle) to the Independent Labour Party, and thereby to Labour itself. Socialist circles were relatively small; a few well-placed individuals could to immense good or equal harm.

In 1883, the year of Karl Marx’s death, his daughter Eleanor Marx began the relationship which would define her life. Her lover was a secularist, Edward Aveling, a movement lecturer. Right from the start, there was something calculated about his interest in Eleanor – Aveling owed money to his comrades in the secularist milieu; he proposed his relationship to Eleanor as a financial transaction in which he would sleep with her, and join the socialists, and she would use her inheritance from her father to clear his debts.

Aveling waited until after he had moved in with Marx before telling her he was already married. He gave her an explanation in which his wife Isabel was the villain of their marriage. It had broken down, he said, after she had abandoned him for a vicar. Eleanor suffered the disappointment of Aveling’s news without complaining. She told her friends they would be “true husband and wife,” combining love with a shared political vision.

Within months, Eleanor writing to friends to complain that Edward was accumulating new admirers. In a June 1885 letter to a friend, the novelist Olive Schreiner, Marx noted that Edward was ignoring her, “You do not know … how my whole nature craves for love … Edward is [dining with friends tonight] and went off in the highest of spirits because several ladies are to be there. I am alone … I am so tired … the constant strain of appearing the same, the constant effort not to break down, sometimes becomes intolerable. How natures like Edward’s … are to be envied, who in an hour completely forgets anything.” As Marx’s biographer Yvonne Kapp puts it, Marx “could not rely on him; she did not honour him; but she did love him. And nothing could shake her loyalty once given.”

For 15 years, Eleanor and Aveling went everywhere together. They were members of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and then of William Morris’s Socialist League. Marx helped organise the 1885 International Socialist Congress in Paris. She and Aveling travelled across America, raising funds for leftists persecuted under Germany’s anti-socialist laws.

Isabel Aveling’s early death raised the possibility that Edward and Marx might wed but instead he started further affairs. Aveling promised to marry Eleanor but failed to deliver – until, instead, in June 1897, he married a much younger woman, Eva Frye. Eva first appears in the socialist press in January of the same year. By now the Socialist League had folded and Aveling had rejoined the Social Democratic Federation. The SDF paper Justice reported a night of entertainments in Wandsworth to fund the Federation’s science classes. The events were organised by “Alec Nelson” (a pseudonym for Aveling), with Frye performing in one of his comedies, The Landlady.

In June, Marx was busy organising an International Congress of coalminers in London, arranging the translators and looking after European guests. When Aveling married Frye at the Chelsea Register Office that same month, he used the assumed name Nelson and reduced his age by three years on the certificate. “Aveling’s furtive marriage,” writes Kapp, “is to be explained only by the supposition that the young lady refused to go to bed with him unless he married her, alternatively that she was pregnant or said she was.”

The ceremony brought Eva little joy. Her new husband reverted to the house he shared with Marx after just a week’s honeymoon. He was suffering from an abscess in his abdomen, had no money and could not afford to rent a new home. For some eight weeks he was living with Eleanor but fleeing on occasion to see Frye, all the time keeping their marriage secret. At the end of August, he briefly moved out; in September he returned. At last, he told Marx that he had determined to leave her. She described the conversation to a friend, “I am face to face with a most horrible position, utter ruin – everything to the last penny or utter, open disgrace. It is awful; worse than even I fancied it was.” Eleanor never explained directly what his threat was. Historians have speculated that he threatened to reveal that he and Eleanor were sleeping together outside marriage or that her father Karl had had an illegitimate son Freddy with his housekeeper Helen Demuth.

Whatever the exact content of Aveling’s threat, Eleanor took it seriously. Despite Aveling’s cruelty toward her she did not throw him out. Rather, she stayed with him begged for time. When she visited her sister in France, Aveling accompanied her. Publicly, it was as if she had forgiven him. Privately, she was devastated. He repeated his demand that Marx finance his new life. He remained ill. In October, he suffered influenza, then pneumonia. In December, he had a temperature of 103 degrees.

Aveling’s physical health was deteriorating. Doctors warned that he did not have long to live. By March, Marx was able to get Aveling to walk only with a stick and there was “very little hope of ultimate recovery”. Aveling expected Marx to devote her every waking moment to his care even after he had told her that he wanted to leave.

On the morning of 31 March 1898, Eleanor received a letter. Her maid Gertrude Gentry was vague afterwards about its contents, saying only that it “threw a very discreditable light on a certain person.” There is little doubt that the letter concerned Aveling. Eleanor’s biographers have surmised that only now did she learn that Aveling had married Frye. Later that same day Marx drank a draft of cyanide. By the time a doctor arrived, she was dead.

When she try to sift apart and sort the many different creepy, misogynist and predatory men who were active on the 1880s left, some are genuine mysteries. HG Wells, for example, is a puzzle, with his combined beliefs that he was the great sexual adventurer of his age while the women around him (his wife, his mistresses) were all, within hours of his meeting them, looming or actual disappointments. Did he really never grasp that the one thing all these angry, marginalised, woman had in common was him? Aveling is much simpler by comparison. He just thought that everything in life which mattered - money, love, pleasure, all of life - was his. And if a woman had those joys in any amount, then he was entitled to take from them.

Eleanor Marx’s biographers (Yvonne Kapp, Chushichi Tsuzuki and Rachel Holmes) all accept the verdict of Marx’s inquest, that she died by suicide and that Aveling was the effective but not the immediate cause of her death. But the informal opinion of her contemporaries was that this was not how she had died.

Edward Aveling’s biographer, the playwright and historian Deborah Lavin sees it differently. Her reasons for accepting Hardie’s opinion include the following. It was Aveling not Marx who approached the chemist who supplied the poison which killed her; Aveling was in the house on the day of Eleanor’s death; he then lied and pretended he hadn’t been there. His testimony to the inquest was plainly evasive, as was the testimony given by Eleanor’s maid, Gertrude Gentry, the key witness. Meanwhile the coroner had decided early on that Aveling was innocent and asked only desultory questions of him. From this pattern of denial and deceit, Lavin infers that he must have applied the poison which killed her.

This opinion was widely held at the time. The reaction of contemporaries shows that many of them suspected Aveling of having actually murdered Eleanor. Across the otherwise bitter dividing lines of the late-Victorian left, there was unanimity among the socialists who made up Marx’s adopted family in blaming Aveling. The trade unionists’ newspaper Reynold’s attributed the “suicide of Karl Marx’s daughter to [Aveling’s] heartless treatment.”

On 9 April, the German revolutionary Wilhelm Liebknecht wrote to Eleanor’s sister Laura, “These are terrible things they are saying about Aveling,” Liebknecht wrote. Another friend, Eduard Bernstein, had seen Aveling on a train with Frye, “Why the rogue had returned to Tussy [Marx] at all we can only suspect but for me it is sure that it was her money.” He wrote that Aveling should be tried for murder.

Keir Hardie, future founder of the Labour Party then an activist in the Independent Labour Party, wrote of Edward Aveling: “The brute has killed her – though she was not a thing he loved – he is incapable of loving anything outside his own dirty, cowardly, hide.”

Eleanor Marx was the route into English educated life for some of the most advanced ideas that were gaining ground in Europe. She translated Flaubert and Ibsen into English. In the workers’ uprising of 1889 - her generation’s 1968 - she acted as a mentor to the gasworkers’ leader Will Thorne, who she’d taught to read. Under her influence, the union adopted a revolutionary constitution: no benefits but strike benefits. In contrast to the craft unions, who were 60 years from admitting women members, the Gasworkers encouraged women to join, which they did in large numbers; Marx sat on the union’s first executive. She was known, indeed loved, in the workers’ international and spoke at the great rallies which lunched the campaign in London for the 8-hour day. Thinking of all the connected people around her which make no sense without Eleanor’s presence to ease the path: Hardie’s leadership of the Labour Party, for example, his radical, almost self-defeating support for the suffragettes, which would not have happened without Eleanor or the influence on him of her Socialist League or of his own ILP.

Ideas flowed from her pen; perceptive, incomplete. She wrote a review of August Bebel’s best-seller Woman in the Past, Present and Future. Then, when Bebel had been translated into English, she wrote ‘The Woman Question’, to win her comrades to the idea that socialism and women’s equality were a single cause. The woman, Marx wrote, “like the labour-classes, is in an oppressed condition; that her position, like theirs, is one of merciless degradation. Women are the creatures of an organised tyranny of men, as the workers are the creatures of an organised tyranny of idlers.”

Marx could have been the route through which many further ideas had come; should have been our Zetkin, our Luxemburg.

But where does insight that leave us? It’s hard not to be torn between two competing impulses. One reflex is anger. Marx was just 43 years old when she died; had in front of her half a lifetime to expand and deepen her ideas. It’s not just her we lost, but all those who might have come after; all the organising and thinking they’d have done. One man, Edward Aveling, was able to undermine an intellectual tradition before it could begin. But does it matter, really, that Eleanor was capable of great things? Shouldn’t it be enough to remember Aveling for his cruelty, wouldn’t he still have been a monster, if his victim had not been Marx but the unknown actress, Eva Frye? To say that Aveling killed a socialist whose ideas might have changed the world is to give him a grandeur he doesn’t deserve. We will not allow it, not in his case, nor for all the other men who’ve bullied left-wing women into sleeping with them.

Edward Aveling died on 2 August, four months after Eleanor. The Social Democratic Federation’s newspaper Justice reported Aveling’s death by noting the brief period by which he had survived Marx, “It would be idle to affect grief over the demise of a man who we cannot help regard as being responsible for her death.” While few of the sexual perpetrators that the British life has produced since 1900 have been guilty of such crimes as Edward Aveling; he was hardly the last man to treat women as his private possession, or to see the socialist cause as his own fiefdom.