For some time, I’ve been collecting novels which focus on the far right. One of them is a book published in 1938, Minimum Man, published under the pseudonym Andrew Marvell. That book tells the story of a British fascist, Jellaby, who stages a successful coup. He is brought down by alien invaders, a race of short (12-inch tall), intelligent, humanoids. The aliens appear to have no super-abilities, save for one, telepathy. Equipped with it, the minimum men swiftly kill 26 leading members of Jellaby’s Party of New Freedom. Jellaby is driven out of power. Their victory over him, the novel implies, brings about a temporary calm before they take on the entire human race.

The author of Minimum Man was Howell Davies, a BBC scriptwriter and sci-fi fan who was a friend of his fellow novelist John Wyndham from the mid-1930s onwards. Wyndham’s 1957 novel The Midwich Cuckoos – the source material for The Village of the Damned, which was made into a film three years later – imitates Davies’s antagonist. Once again, the enemy is a collective of small, quiet, but powerful strangers who operate as a silent hive-mind. The one significant tweak is that the society of telepathic humanoids are no longer short because they are a separate species, but because they are children and not yet fully grown.

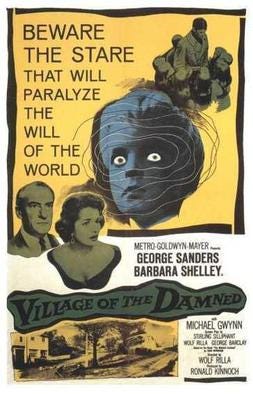

The film begins with a phone call, middle-class stuffed shirt Major Alan Bernard, played by veteran British character actor Michael Gwynn, is hoping to speak to his brother-in-law, the Professor Gordon Zellaby, the actor George Saunders. (A brilliant philosopher and author, Zellaby is evidently named after the villain of Minimum Man, Jellaby). Midway through their call, Zellaby falls to the ground and the phone operator is unable to reconnect him. His collapse, viewers learn, is not an individual act, but the product of a collective sleeping sickness which affects everyone even the animals in the fields around the village where he lives, Midwich. A quiet, small, southern English town, its inhabitants wake up after several hours.

Not long afterwards, the villagers learn that every Midwich woman of suitable age has become pregnant. Everyone is affected: women whose husbands have been away from home for over a year, even virgins are due to give birth. What happens next is the sharpest divergence between the film and the novel. The former lasts a mere 77 minutes, requiring any number of cuts from the book. The scriptwriters cut female characters, their dialogue and their choices. Wyndham, by contrast, grasped that an unintended pregnancy could be a disaster for the person experiencing it. Eight characters in his novel attempt informal abortions, through hot bath, falls, or taking aspirin or other chemicals. In the book’s next chapter, the five dozen pregnant women meet – with all men excluded from their discussions – and plan what they are going to do. They don’t want outsiders talking about them, they are determined to keep the press away. They resolve to go on with the births. (The films passes over all this).

Once they’re born, the children are alike, with blond hair, golden eyes, narrow fingernails and back-combed hair. Between each other, they have a telepathic bond. They treat all unwanted contact, even the accidental, as a mortal insult. They are also able to impose their will on other people: their eyes are enlarged and glowing while they hypnotise their victims. As they age, they take on a precocious physical size, dress and speak like adults.

Midwich, viewers learn, is just one of several towns to have gone through a similar invasion. In one Australian town, the children all died on birth; members of an Eskimo killed their children; in Mongolia, both the children and their mothers were murdered. In a Soviet town, the children were at first welcomed – the state later killed them with a nuclear strike. The telepathic Midwich children learn for themselves of this latter holocaust. Increasongly fearful, they clash with the Midwich villagers, causing one to burn himself alive. Local tensions combine with the news of international events, setting up the film’s central dilemma; will this town of English villagers (and in particular, Bernard and Zellaby) respond like the rulers of the Soviet Union and kill the arrivals, or will they recognise that the children have a right to live, and reach some accommodation with them?

The comparison with the USSR would have been of particular importance to viewers, in a second sense that the Midwich children are (among other things) a metaphor for the menace of Communism. In 1951, sometime CIA stronger Edward Hunter had published, Red China: the Calculated Destruction of Men’s Minds. It popularised the message that China was planning to unleash new forms of psychological warfare against the West. In 1956, Hunter’s international best-seller follow-up, Brainwashing: the Story of Men Who Defied It, described Communist propaganda techniques as being intended “to change a mind radically so that the owner becomes a living puppet”. That idea of a person turned into a marionette captures the interactions of the Midwich children in relation to David, their spokesman. His personality is so strong that it leaves the others passive behind him, empty and incapable of speech.

In the film, Zellaby takes responsibility for the children. He senses their power and determines to kill them. He proposes to do so by setting off a bomb in the classroom where the children gather for lessons. This is a suicide mission. To succeed, Zellaby must also find a way of escaping the children’s ability to see into and take control human minds. He imagines a brick wall and hiding his thoughts behind it. In the film’s dying seconds, the last moment of tension comes from the conflict between his ability to conceal his thoughts and the children’s evident skill at unravelling them. We see the wall again and again. For several minutes, we do not know which determination shall prove the more powerful, his or theirs.

At the level of appearance, there is a similarity between his conduct and the children’s. They manifest their power through a combination of keeping silent and yet communicating with one another. He shows his strength through plotting furiously and yet never saying what his plans are. Silence is a common consequence, yet Zellaby is not a hive-mind, he has not been brainwashed. He reaches his conclusions out of patriotism and male duty - they are just the right thind to do.

The message which The Village of the Damned tells its audience is that there still exists in Britain a class of heroic people, “men”. They are virtuous, in a first sense, through their participation in a good war. They share the memory of the conflict, the events of which they have never revealed to mere civilians (women, or those who were children in wartime). They have come back from the fightingand repressed their emotions of suffering and guilt. In keeping these experiences and feelings private – hidden, as it were behind Zellaby’s brick wall – they have been heroes a second time, in that they have prevented the people they love from having to form the understanding the way that all they find good about postwar Britain (its domesticity and community), depends on the fact that their country won the war. It is built, in other words, on a foundation of men shooting guns or dropping bombs, and the people they hit with those munitions (mainly, but not only, German soldiers) sobbing as they died. It is far better that they should not have to confront this reality.

The film’s message is that all that emotional repression has been healthy. It has left men in an appropriate condition of stiltedness and silence, which they would have to draw on again if faced with a new threat – alien or Soviet.

Of these two connected messages, the first is strongest. The connection to the recent war is more powerful than the link which The Village of the Damned is also drawing towards anti-Communist conflicts in future. Viewers see many reminders of the recent war – the soldiers who occupy Midwich at the film’s start, the uniform in which Bernand goes everywhere, the officers who by the film’s ends are threatening to detroy the village. The alien children, by contrast, neither look like any real-life Soviet figure, nor show any strong loyalty to that state.

I want to end not in 1957 but today. Half a century ago, it was possible for people who were instinctive conservatives (churchmen, officers, professors) to insist that their politics was a noble and virtuous dogma of serving the collective. When Europe and the world had threatened to fall under the sway of fascism and genocide, hadn’t they put their bodies on their line to protect democracy? Zellaby is their representative in the film, entitled, rich, poorly equipped to tell his wife he loves her, and yet taking at his own cost the choice that will save hundreds of lives.

Often, on the left, we see the legacy of Churchillian conservatism as mere humbug. He was fighting to save the Empire, wasn’t he? Well, yes, he was. But if Churchill’s children are going to jump sides, and behave as Hitler had won the war - that won’t make politics any easier for us.

If you look at the centre-right today, the message is the opposite to that of the 1950s. That, if there is a genocide, then those responsible for it should be lauded as heroes. That if there are people on the street threatening to hurt other people, because they are trans or Muslims, then conservatives are on the side of those who threaten or initiate violence. If this generation of conservatives were faced with similar events to the Midwich children, they would be offering the latter a united front – enslave the poor villagers, so long as the rich remained in charge.

Through this summer, Keir Starmer has sought to position Labour as a party fit for bigots. At least, he has been resisted – the party’s polling has collapsed. Kemi Badenoch has tried a similar move on the right, and no one has complained. Her only competitors on the right woulkd go further, faster, to emulate Trump. Part of the reason why politics has felt so broken has been the solidity of the convergence between centre- and far right. This should be as big news as Labour’s moral collapse.

There was a delightful and informative biography of John Wyndham a few years ago by Amy Binns

https://amzn.eu/d/7Ub0uLl

Wyndham's anti-discrimination, and women with strong roles, themes had a significant if subliminal influence on me personally - this biography revealed the roots of his attitudes, equality for women, and other insights in the source of his inside knowledge of the politics of the anti-communist space-race which gave us his 'Outward Urge' in his role in the British Inter-Planetry Society for example ...