This is the first of what is going to be a small group of pieces on the theme of errors on the left, by which I mean mistakes, petty treasons, small steps of moral cowardice. I’ll be asking where these failures come from; and where they leave people who you might have known, liked, even loved. Should you celebrate a Marxist in another generation, if you’re aware of all the mistakes they made? If there are any particular rogues who readers would like me to focus on, then contact me - and I'll see what I can do.

Two weeks ago, I went to a meeting of the new campaign, We Demand Change. There was a speaker from the Stop the War campaign, as well as Islington’s radical socialist councillor Ilkay Cinko-Oner, and Andrew Feinstein who took 25,000 votes off Keir Starmer in the last election. In a late cameo, even Jeremy Corbyn came into the room. But this was an event organised by my former comrades in the SWP. So, Feinstein, Corbyn, all of them, mere mediocrities in the organisers’ eyes, were expected to play a subordinate role compared to the lead speaker, Lewis Nielsen the SWP’s National Secretary, the new incumbent of Martin Smith’s old job.

I tried to pay attention to Nielsen’s speech, had my notebook open to take notes. For the sake of people I’ve known in better times – for the sake of Nielsen himself, who I remember coming to one of my own talks five years ago and sitting in the back row, gurning for an hour, before denouncing me and the other speaker, shock-headed Neil Faulkner, as "pessimists"… I wanted it to go well. Give me an interesting insight, I was willing him – a joke, anything – borrowed, blue, I won’t care. “We have seen a magnificent Palestine movement,” Nielen said at one point (his comrades applauded that line cautiously), “we have seen a game-changing anti-fascist response to last summer’s far right riots” (there they slapped their hands together as if to protect themselves against the midsummer cold). By Karl Marx and all that is profane, this was uninspiring stuff. No jokes, no unexpected turn of insight, no observation that pooled anyone’s collective wisdom. No red rope to pull you upwards, no promise of emancipation, no hope.

Marxists of my generation have an annoying habit of telling anyone who’ll listen that politics, like sex or music, was better when we were young. The left-wing speakers of our early twenties were sharper and funnier than their counterparts today. In Margaret Thatcher we had an antagonist who made your pulse quicken; unlike Keir Starmer who is so militantly uninteresting that not even the people he would like to jail (peace activists, climate protesters, trade unionists) can summon the rage to hate him with the fury he deserves.

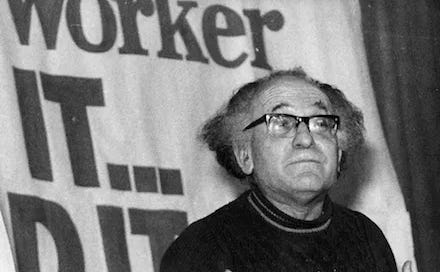

The thing is – we aren’t just old people nostalgic for our youth. If you look just at the SWP it really is an inferior product compared to the same party 30 years ago. You had, as leader of that group, Tony Cliff: a man shaped by political conflicts two thousand miles away, who had plenty of experience of life outside the party bureaucracy (has Nielsen have been employed by anyone except for the SWP?). Cliff had been a minority within Britain when he came here: on the left, not a Labourite when that party was at the peak of its influence, nor a Communist when there were 50,000 of them. He’d sided with a despised minority, the Trotskyists. He’d been a minority tendency (a “state cap”) even inside that part of the far left. He had worked in open parties, he had worked in Palestine under clamdestine conditions of widespread censorship. While the SWPers you meet today treat politics as an allergen, while they argue within every campaign they join for a lowest-common-denominator politics which wouldn’t upset a passing Liberal peer – deep into his 70s Cliff would walk around the SWP’s Marxism conference, looking for anyone who disagreed, would talk with them for hours if the reward of that time was that it would lead to one more revolutionary. He enjoyed the argument.

Leaders of left-wing parties impose on their groups a personality. Cliff, and the SWP, were desperate to win new members, determined to escape the “swamp” of failed left initiatives, suspicious of academic authority, keen on dramatic acts of street theatre, willing to give up time, energy and money in favour of a loved cause. He, and his organisation, were willing to provide a social life for people away from home for the first time, were loyal to the comrades who saw the need for a certain task, brutal to those who didn’t, capable of arrogant boasts and moments of self-deprecation, always eager to improvise. Cliff spoke quickly, rejecting the lugubrious tones of the leaders of rival groups. He had the concentration of an obsessive. When it came to choosing a cause within the left, he was flighty, hunting for the campaign which was running out of steam and urging his members to abandon it for the next opportunity. If he was alive today, he would have been telling socialists a month ago to drop everything and campaign for trans people, a fortnight ago to burrow within the proposed new Corbyn party and, this week, to give up everything else and agitate like hell against the proscription of Palestine Action. If that meant taking people away from campaigns in which they were rooted, who cares? His focus was always on the most immediate: the now, the now, the now.

Over time, Cliff reverted to a one-factor theory of history, in which the one social fact worth counting was not the rise of democracy, nor the innovation of capitalist technique, nor even the interaction between the rising power of social groups and the limits of the society which bound them. Rather, the key to everything was the membership of the Marxist party so that you might look at international events and judge one seemingly-historic protest deficient (there may have been two million people tearing down the door of that country’s parliament but only 50 of them were members of a Marxist party), and another compelling (there were just a hundred people on a one-day bureaucratic strike, but 51 of them were in a party). In all imaginable circumstances, a party of fifty-one counts for more than a party of fifty.

He had his flaws in, but the Cliff of the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s was not unhappy. The movement as a whole may have been shrinking, but we were becoming more influential within it. That was enough for him. His supporters meanwhile were swept up by the promise of revolution. Listen to Cliff, and you’d believe the great change was coming.

Those of us who are Cliffites and still do revolutionary politics - all these years later. That’s on him, his legacy, his inspiration. We owed him a credit.

So, how could a party like the SWP of 30 years ago – a group with working class autodidacts in every branch, and an abundance of talent among its theorists – have produced the dull, stale, sect of today? Events have made a difference: the 2013 Comrade Delta rape crisis, before it the split with Counterfire. Before them, though, and more fundamental still was the slow degeneration of the organisation in the decade or so after Tony Blair became Prime Minister. Many habits of today’s top-down SWP – the extraordinary gulf between the full-timers and the members, the idealisation of leadership, the bureaucratic practice of tailing unions leaders and celebrities – date from that period, in which the SWP was led by John Rees, Lindsey German, Martin Smith, Alex Callinicos and Cliff. Each of the first four – although they are in two different parties today and one is in no party at all – agreed on the most important thing: a style of leadership which imitated the absentee landlords of the middle ages.

Cliff wasn't like that: he sat in his kitchen, he welcomed visitors. The party was his life; he couldn't separate himself from it. You could talk to him about the party, how aloof the other leaders were. You could see for yourself how isolated he felt, how few comrades he trusted. There were a tiny cluster of manual workers still in the SWP - the likes of Chris Clark in Hackney. Cliff befriended those last blue-eyed boys desperately, then turned against them with even greater impatience than had been his habit. Duncan wasn't talking to him, few of the old guard were left.

He had always made it the most important line in any public talk he gave to say, “You don’t tell lies to the class,” but now a Cliff-founded, Cliff-inspired SWP with Cliff-picked leaders was telling lies at every opportunity, insisting every march was a success, claiming that every small initiative was the leadership’s inspiration. The SWP was becoming a party in many respects worse than its founder and unlike him – and yet it degenerated with him in charge.

In the official SWP-approved biography of Cliff, the historian Ian Birchall hints at some explanations. He writes of Cliff “standing back” from certain political tasks as he aged (p 516), he writes of “the weakness of the movement” (p 518) as the cause for a certain narrowing of Cliff’s imagination, a focus on 1917 as if that one moment changed everything, even though that revolution was – like Cliff – past its 80th birthday. Cliff was drifting away from the SWP, Birchall writes, to focus on the organisation’s sister parties in case they came good (p 527).

The most important issue was this. At the start of the 1970s, Cliff had deliberately narrowing the SWP's predecessor IS, disdaining its previous attempts to ally with surrounding groups, his own Luxemburgiam, turning that organisation into a Leninist party. For a couple of years, the tactic had seemed to show exhilarating success - in 1972, Socialist Worker sold at times up to 50,000 copies a week, many times more than before or since. But, as time wore on, Cliff misread and came to depend on that moment, glorifying it in his biographies of Lenin and Trotsky. He did so, even though the rewards of that gamble in terms of teaching habits of obedience and loyalty inside the party looked ever less enticing as the 1990s wore on. The SWP in 2000 had around three times more members than it had 30 years before. But the party was in most other ways much smaller: the original talents had left, their potentiual replacements were permanently excluded for fear they'd disagree with the leadership. Its publications were dull, branch meetings were worse.

Birchall notes that in 1968, even as Cliff was formulating his turn to Leninism, Cliff was "overtstat[ing]" both the good and the bad in the world around him - telling one audience that within 7 years there would a revolution or a completed counter-revolution. "If I am wrong, I see you in the concetration camps" (p 289). He writes of the “impatience” (p 292, 520) which underpinned Cliff's Leninist turn. He uses the same word when describing the 1975 split in IS which saw the leadership throw away much of the group's industrial cadre, and cemented the organisation as one in whcih no permanent disagreements would be tolerated (p 404).

Birchall hints at various points that age stood behind some of Cliff's decisions. He describes the terrible blow of the defeat of the miners, falling as it did just before his 67th birthday. "The hope of revolutionary change within his lifetimes, wich he had belived in until very recently, had now become remote" (p 481). Of Cliff in the 1990s, Birchall writes, "Imperceptibly but remorselesly he was growingolder" (p 525). Birchall does not addres the leadership in Cliff's last years and months, but it is legitimate to ask whether Cliff's selection of the Rees-German-Smith leadership to take over after him was a product of age. Going into his 80s, Cliff needed to believe that the revolution would succeeed in his lifetime. For all Cliff's opposition to lying, at the end of his life he found it easier to appointed people who flatered him, who insisted that his every initiative was a success.

Cliff made mistakes; we live with their legacy. I haven’t written this piece to denounce him. He continues to shape my politics in certain basic ways; just as the idea of a pure Cliffite party today, a quarter of a century after his death, seems almost a joke to me. How would it recruit people who never knew him? I try to imagine Cliff alone with Lenin and Trotsky, without Rosa Luxemburg, without CLR James; why would anyone think that narrowing of Marxism and ignorance of allied traditions was in any way desirable? It would be like having a family with your father and grandfather but without your brothers, your sisters, your cousins.

Seeing Cliff as the person who began the betrayal of his own legacy is not an insult; it is to treat a fellow Marxist as human. It is to forgive the people around you when they make lesser faults – when they improvise an opinion then later reverse it, when they’re unkind in something small. But if they make greater mistakes, then say so, shout about them, if necessary. There’s nothing principled about forgiving when the right demand is justice.

In relation to Tony Cliff, I’m saying that we should explain it all. I’m insisting on keeping the good, passing without rancour over the bad. But don’t forget that some bad was there too.

________________________

If you enjoy my writing, my novel The Story of Jenny Greenteeth tells of a student in London who befriends a violent water-nymph, a canal-dweller, the incarnation of revolutionary violence. It is published on 27 August. The novelist Tina Baker calls it, “A dark feminist fairytale - creepy as fuck!” You can pre-order it here: https://shorturl.at/9yj6D.

Thanks for this David.

When you talk about the SWP’s leadership group from the Blair era onwards - “John Rees, Lindsey German, Martin Smith, Alex Callinicos and Cliff” - is there a reason you don’t include Chris Harman’s among their names? Or anywhere else?

I couldn’t help but notice.

Talking about the SWP having become a joke:

https://www.facebook.com/100014406731876/posts/pfbid0gFRHhyc3kZm2eREsKiLxoTtFzWruq5akCx6DV2sp5J1sS7rKK6vme1B4UjWv858al/?app=fbl